“I get on with them well enough, but these people were my mortal enemies twenty years ago.”

Thus spoke Tom (whose name I’ve changed for his privacy), yr. correspondent’s guide for a Troubles-themed tour of Belfast. Tom, ever-affable, is a former-Catholic and forever-republican; he offered the sentiment above when I asked about a unified Ireland, which, he ceded, is (marginally) more likely after Sinn Fein’s historic triumph in the Northern Irish Assembly.

But one anecdote does not an appropriate dispatch make, nor does it effectively communicate the experiences and realities characteristic of Belfast today—nor does it answer why I chose to start my G.I.T. in Ireland. To unpack the latter two concerns, and to achieve the former aim, let us turn our attention to Dublin.

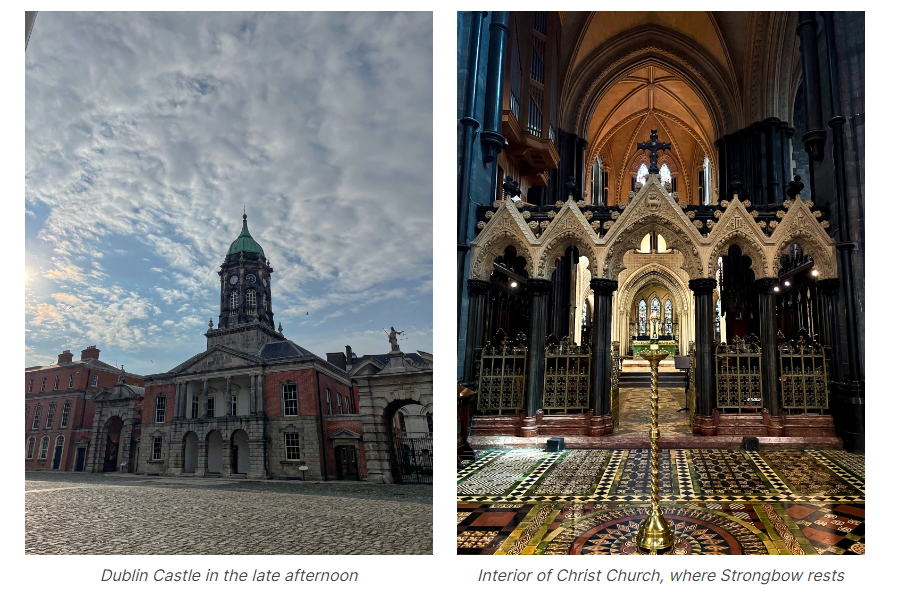

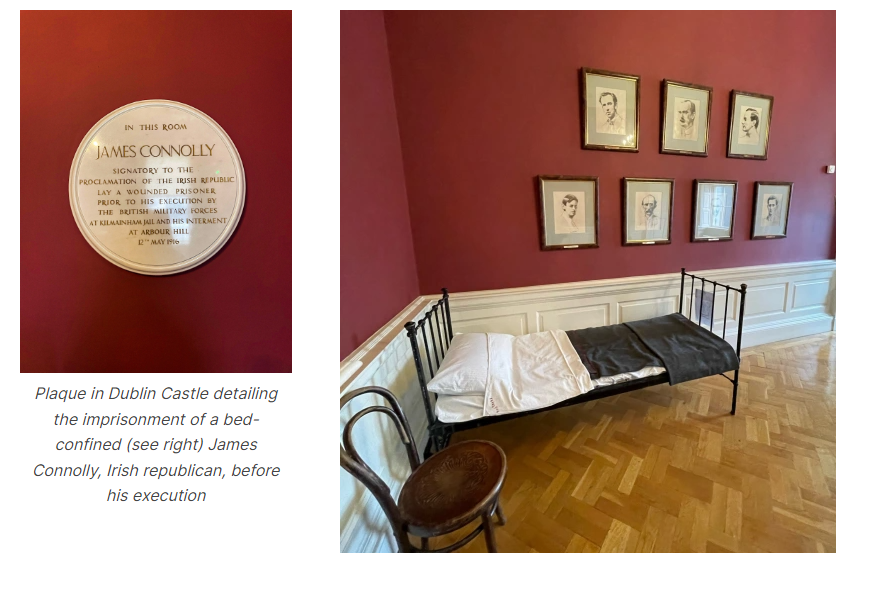

Dublin’s history, as yr. correspondent and his associate learned at its castle, begins with the Vikings, who, upon arriving in approx. the 9th c., made it an administrative center on the River Liffey and who became, albeit more hygienic, as Celtic as the Celts. Therefore the true shake-up on the island was the arrival of the Anglo-Normans in the 12th c.; led by ‘Strongbow’ Richard de Clare (interned in Christ Church), they deposed the King of Leinster whilst balancing a separate war in France. Nevertheless, the imperial designs for Dublin only reached a fever pitch in the Tudor period, with the castle acting as the crown’s ‘nerve center’—supporting religious conformity, land confiscation, and, eventually, the plantation of Ulster (foreshadowing!).

All this to say: Dublin is peppered with sights, scenes, and sounds that demonstrate the success and failure of a colonial project. We visited on our first day the Garden of Remembrance, a touching monument to those who died pursuing ‘the vision’ of an Irish state: “Bondage became freedom,” its back wall read, “and this we left to you as inheritance. … O generations of freedom remember us, the generations of the vision.” Further, the Dublin Spire, an imposing, metallic, 120 m. tall pin, served as our North Star, pointing us towards city center; it stands where a pillar honoring Horatio Nelson, the esteemed English admiral, once stood—that is, before its destruction by Irish Republicans on political grounds. In contrast, Dublin’s most famous cathedrals (St Patrick’s and Christ Church) are Anglican, depicting the uneasy, but symbolically gainful, process of religious conformity.

But, since their hard-earned independence—for which many rebels were gaoled at Kilmainham and/or extra-judicially killed—the Irish and, by extension, Dublin have excelled in cultural regeneration, and have ensconced themselves in Europe. A trip to the National Gallery proved as much: it boasts a strong collection of Irish artists, like J.B. Yeats’, whose later, expressionistic work feels almost concrete, and William Orpen, whose playful self-portraits have for years delighted yr. correspondent. Equally intriguing was the gallery’s temporary Giacometti exhibit. We received our tickets per chance (a French couple mis-scheduled and handed them to us whilst hurrying to re-book); esp. enjoyable was this rare glimpse into the studio practice of existentialists Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir’s favorite sculptor. (Do view compositions from these artists, and others, below.) However, we saw no pieces of English origin save a typically sensitive and inspiring effort from J.M.W. Turner.

And this painterly discrepancy is illustrative. Dublin and its constituents don’t necessarily dislike the English—when, on our final day, for want of other warm-wear options, I donned my Oxford jumper, not a single snide remark was launched my way. Yet they are dealing with a mix of hegemonic hyper-presence and disappearance: what happens when the dominant power leaves?—what does one do with the keys to their own fate? Most everywhere in our postcolonial world begs such questions.

One place where they are not: Belfast. For the British haven’t left yet. In other words, if, presently, Ireland is de-colonizing, their northern neighbor is instead grappling with the economic, political, social, and religious factors underpinning colonization. But you wouldn’t be privy to that immediately: realizing it is akin to excavation.

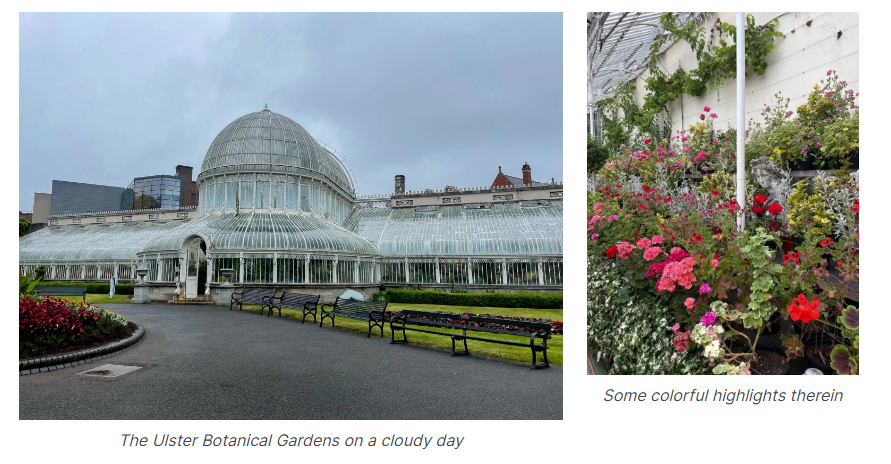

For instance, the Ulster Museum, to be commended for its natural history resources, art collection, and botanical gardens, was sparse in its Troubles-related content, much to the chagrin of a museum employee who grew up in a Belfast suburb and with whom we chatted for a half hr. Or, another ex.: there are shops for the two largest Scottish soccer clubs, Rangers and Celtic, in the city. Why?—well, the latter was founded by Irish immigrants; the former refused to sign Catholic players well into the 20th c. Thus these teams are, surprisingly, interlocutors in a conflict a sea away: i.e., loyalists are Rangers fans, republicans back Celtic. This, of course, was not immediately clear to yr. correspondent: it took digging.

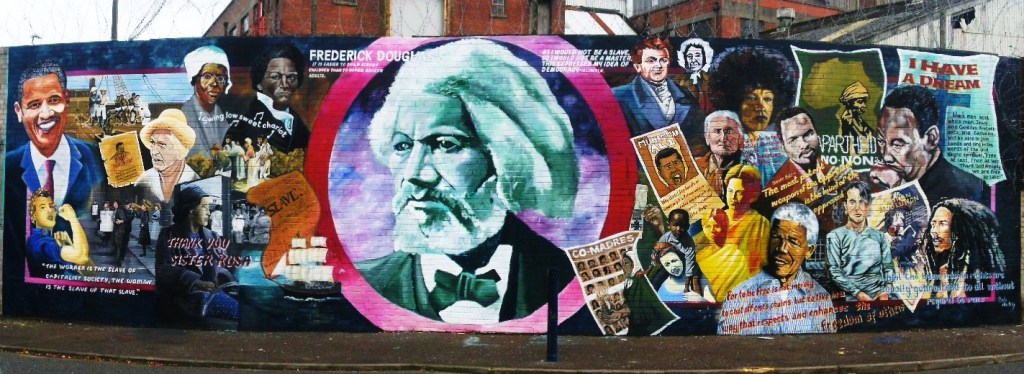

The point belabored, it’s wise to return to our excavator extraordinaire, Tom; he, during our tour, unearthed much of now-quiet Belfast’s ‘seedy underbelly’ (his words), as well as its less-than-settled past. While laymen understand the Troubles to be sectarian—Catholic v. Protested—Tom insisted it was rather economic and political: the English hanging on to a critical industrial outpost, not to mention the legitimacy of their isles-empire (which [callback] properly started with the Ulster plantations!). Altering the perception of the clash (the terms of discourse) was the purpose of Bobby Sands’ famous hunger strike, noted Tom—so too of the republican murals, which link Ireland’s struggle to worldwide social justice causes, incl. the U.S. Civil Rights Movement.

And it seems, to close, that the nationalists are ascendant (see, again, Sinn Fein), if not outright victorious, shifting the issue in N.I. from cohabitation to reunification. Such a prospect, Tom thinks—and as Irish/Dublin’s history indicates—, will prove challenging. Shankill Road, a loyalist neighborhood, remains marked by murals of William of Orange, Stephen McKeag and other UDA members, and, as Tom put it, the ‘Mona Lisa of terrorism’ (in which the barrels of Ulster militants eerily follow passers-by). All of these are signals of the strong cultural and emotive push from unionists to hold on to what might be soon lost. This is reciprocated (economically, at least) by the British government: a new trade protocol for N.I., released this week, will ‘harden’ the Irish border and exasperate existent division.

Potential solutions to this end are difficult to suggest with such limited experience, and such rapidly evolving circumstances. Nonetheless, familiarity with this region and its complications are essential as I work to embody the spirit of the Marshall scholarship and Doc Ramsey: an awareness of our shared humanity, a keen eye for the factors (systemic and individual) undermining it, and a desire to foster it in myself and others.

G.I.T. Gallery: Ireland and N.I.

‘Fun Corner’: What to do!

In Dublin: sun-bathe at St Patrick’s Park, visit the National Gallery (all of it), eat at Boxty.

In Belfast: take a Black Cab tour, grab a sausage and mash at White’s Tavern, walk around St George’s Market.

Bree’s dog rating:

Dublin: ‘8/10 … too bustling to get a full view unless you’re in a park.’

Belfast: ‘6/10 … a few around but all on exercise walks.’