Pluralism and the Polis

“God created the world, but the Dutch created the Netherlands.”

Or so goes the popular maxim. Indeed, the Dutch landscape demonstrates adept cultivation: from the (once non-native) tulips that have become a national staple, to the canals which prevent the sea from swallowing Holland (and which structure traffic, commerce, &c. in Amsterdam and beyond).

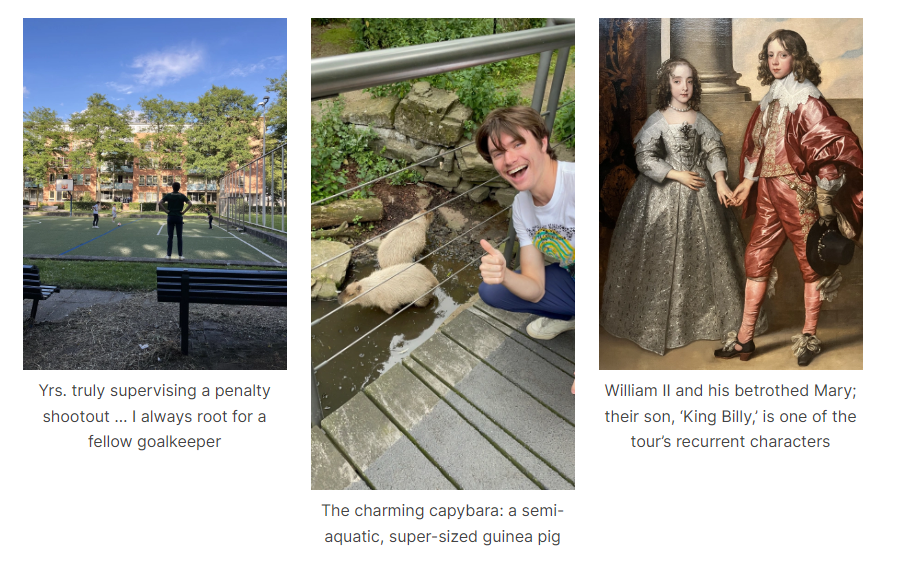

My visit to the capital, moreover, revealed the type of municipal development necessary for achieving a high quality of life—a true joie de vivre. The bike lanes, for instance, are as multitudinous as they’re depicted to be; Dutch cyclists are dizzyingly capable and quick, and their commutes, easy and safe. There also seems to be delicious and gastronomically-diverse restaurants, not to mention green spaces and public playgrounds, peppering any given walking path. Yr. correspondent must add, to this end, the Artis Zoo (which, more than most, strikes me as ethically-maintained), as I met there a duo of capybaras, my favorite animal.

Of course, such structures and institutions represent values that extend beyond Amsterdam’s physical landscape—to the social world its constituents inhabit. This world, despite the rise of far-right, Islamophobic political parties like VVP, is largely understood as plural and tolerant, an artifact of the Netherlands’ historical inputs: rule by rival empires (the Spanish and English) imbued the low countries with contrasting cultures and religion, and later the East and West Indian companies brought with their commercial shipments foreign art and customs. Thus the Rijksmuseum not only hosts rooms of Rembrandt and Vermeer, masters of Baroque painting, but portraits of William II and Mary, mercantile leaders, and the indigenous people such mercantilists exploited.

The latter artistic foci serve as an example of when Dutch pluralism—the equitable division of power, wide cultural toleration—failed to express itself abroad as it did on the mainland, where freedom of conscience flourished. Throughout the 17th c. and on, the East and West Indian Companies, appendages of the state, engaged in brutal violence and oppression in their colonies. Why would this discrepancy arise? We might immediately (and not erroneously) associate it with the extractive nature of any colonial project. But that explanation lies adjacent to the issue’s core: those abused and enslaved were not viewed as persons by their colonizers.

While at the Anne Frank House, a similarly dehumanizing perspective struck yr. correspondent as inherent—and this is not to compare haphazardly—to Nazism. The Nazi occupation of Amsterdam and the rest of the Netherlands, full of both brave resistance and regrettable complicity, along with its miniature—the Frank home and its residents—depict the complex dual-reality European Jews faced. After all, the Franks and countless others, for their fate was tragically unexceptional (met even by my own relatives), were transformed from business partners, neighbors, and friends into an identity-less, existential threat.

This observation is, admittedly, somewhat trite, yet it reveals pluralism’s central question: what practices, beliefs, and institutions, and, by extension, who should be regarded as ‘acceptable,’ worthy of inclusion and human treatment? In this light, I was heartened by a set placards situated next to the paintings aforementioned above, which outlined how foundational slavery and colonization were to Dutch maritime strength and wealth. So too was I encouraged by the concentration on Jewish art outside of WWII, avoiding a fixation on suffering and instead appreciating Jews as part of Holland’s rich artistic heritage. For, these stories are Dutch stories: their past and present consequences must be acknowledged and consulted as tools to expand future boundaries of tolerance and solidarity.

And the matter of who is considered a person also relates to the ‘great idea’ of Munich: the polis. If we grasp the polis as theorist Hannah Arendt did—a place of public interaction and expression—then the limitation of certain modes of interaction and expression within the polis (e.g., the exercise of a religion) could be predicated on denying personhood to a specific class. However, Munich’s layout—its boisterous beer halls, like the Hofbräuhaus, commercial centers, like the Marienplatz, and municipal buildings—does the opposite of limit and exclude, accommodating diverse beliefs, behaviors, and, thereby, people. The New Town Hall is open to members of the public, allowing citizens, who, in a more classical sense, furnish the polis, to rub shoulders with their representatives, and tourists to inquisitively wander about.

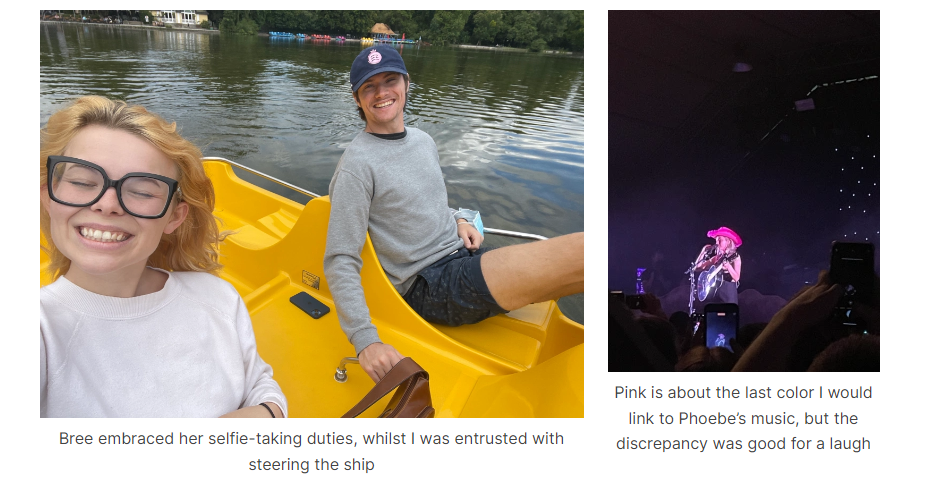

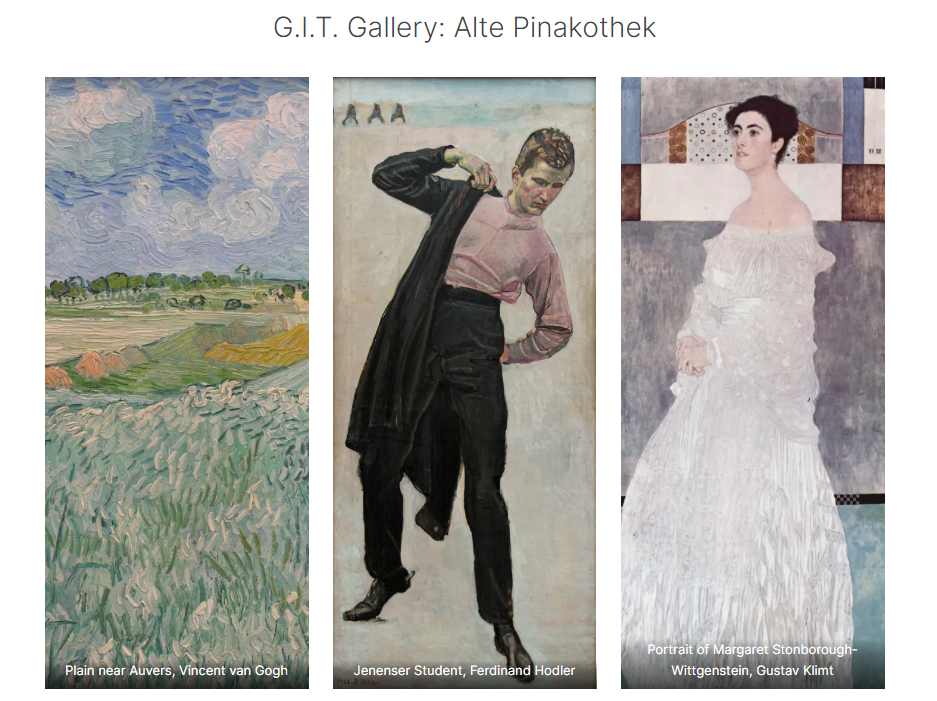

From the sublime to the ridiculous, Munich’s English Gardens likewise welcome all, encouraging expected recreation—walks, football matches, &c.—and the more eclectic surfing and pedal-boating. Or another illustration, re: the variety of creative vigor the city furnishes: the same day yr. correspondent and his associate scrutinized the Alte Pinakothek—where, with tilted heads and brief nods, spectators appreciated masters Reubens, Klimt, and van Gogh (see below)—we watched alternative rock sensation Phoebe Bridgers perform sad ballads in a bedazzled cowboy hat. Developing these niches, from hiking to high art, surfing to songs, helps more people (and their principles, interests, and aspirations) to be incorporated into the polis, which, in turn, forms a plural and human-oriented society.

To be sure, the ideals of Amsterdam and Munich highlighted herein should be sought after by the US, where quality of life and fellow-feeling lag behind the metropoles and nations with comparable socio-economic metrics. But these ideals are a challenge for the Germans and Dutch, too; homeless, for instance, appeared common in both cities, especially for the disabled and mentally ill (whose personhood are often diminished). And, as was previously noted, the two countries have grappled with rising anti-immigrant sentiment and Islamophobia. Still, meeting such a challenge is exactly what pluralism, and a people-centered political climate, demands. It is an obligation: to enlarge the right of personhood to the most meek and disenfranchised, and to protect privileges for those already included in the polis.

To be sure, the ideals of Amsterdam and Munich highlighted herein should be sought after by the US, where quality of life and fellow-feeling lag behind the metropoles and nations with comparable socio-economic metrics. But these ideals are a challenge for the Germans and Dutch, too; homeless, for instance, appeared common in both cities, especially for the disabled and mentally ill (whose personhood are often diminished). And, as was previously noted, the two countries have grappled with rising anti-immigrant sentiment and Islamophobia. Still, meeting such a challenge is exactly what pluralism, and a people-centered political climate, demands. It is an obligation: to enlarge the right of personhood to the most meek and disenfranchised, and to protect privileges for those already included in the polis.

G.I.T. Gallery: Alte Pinakothek

Bree’s ‘Fun Corner’:

Amsterdam: Amsterdam, in short, was an absolute pleasure to visit. Not only were the people pleasant and accommodating, but the food was divine, the intercity travel was easy to learn, and the addition of our dear friend Sophia made it so much sweeter. Dog viewing: 7/10, most notable was a dog whose owner carried her around in a decently sized basket on the front of her bicycle. (Best spots: Artis Park, Rijksmuseum, Sham Oost, Winkel 43, Anne Frank House, Hannekes Boom)

Munich: Nature, music and hearty foods would sum up our time in Munich quite well. The city itself was constantly bustling with vendors, tours, and foot traffic, but you could always find a quiet space in one of the many parks or green spaces. Dog viewing: 9/10, with the aforementioned green spaces, there was always a lovely furry friend to watch running around! (Best spots: Englischer Garten, Hofbräuhaus, Alte Pinakothek, Neues Rathaus)