‘The North’

For the original post, go to: https://greatideastour.wordpress.com/glasgow-edinburgh-and-durham/

Spending any time in the US South reveals it to be an (in)coherent and imagined space. On occasion geographically and socially nebulous, it nevertheless shares (forgive how trite the observation is) a unifying history—the plantation system, Civil War, Reconstruction, Civil Rights Movement—and set of cultural signifiers—accents, music, sport. This, of course, is to simplify the region, to flatten its multi-dimensional contours onto a 2-d page—which I generally deign to do as a once- (and always-) Alabamian.

However, such a simplification is useful inasmuch as it teases out a trans-Atlantic connection: that is, with the English North. Its similar history—compare, e.g., the Harrying of the North to Sherman’s March to the Sea—and collective identity—a Durham Uni. tote familiarly reads, “A boy [can] leave the North, but the North [can] never leav[e] him”—makes it germane ground for exploration. And explore yr. correspondent did; below, I outline my findings in a (slightly) less analytic fashion than my first dispatch.

I believe the North is a ‘great idea’ because it is, like the South, (1) a historically-contingent development and (2) a mentally- and communally-defined place. To this end, there is no better city with which to start than Edinburgh, whose present layout, and (inter)national reputation, was, and is, molded by the political and territorial contests that delimited the North. The vein supplying Edinburgh with much of its architectural and historic richness is the Royal Mile; littered with statues of estimable thinkers, incl. Hume and Smith, it begins at the castle and ends at the Holyroodhouse Palace.

And both of these structures—here I must repeat myself—are products of the North, though well before its existence in the popular vernacular. The former was a critical site for the 14th c. battle(s) for Scottish Independence, and its eventual re-capture erased Edward III’s claim, under the Newcastle Treaty of 1334, to Edinburgh; the latter, the brief childhood residence of James VI and I, the ‘unifier’ of the English and Scottish kingdoms.

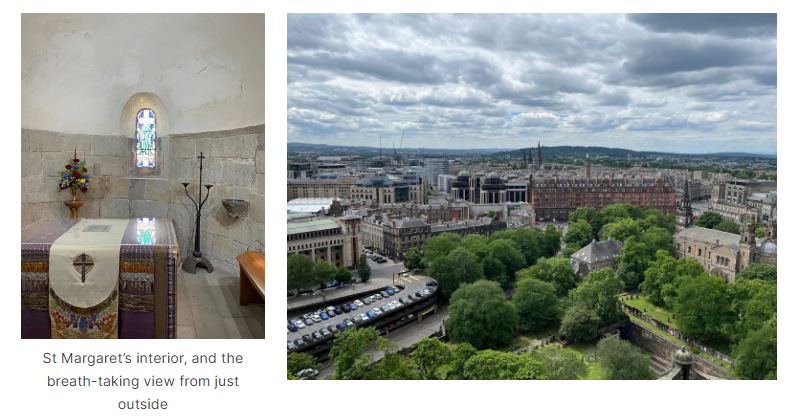

Yet, regrettably, it’s difficult to experience the gravity of Edinburgh—and to become aware of the socio-historical factors underpinning it—today. The throngs of tourists and souvenir shops, as well as the constant, albeit pleasant, hum of bagpipes, interrupt the sustained thought the city merits, transforming it into a strange consumerist spectacle. There are wonderful moments of calm—offered in St Margaret’s Chapel atop the castle, The Meadows, and the Scottish National Gallery—but these seem few and far between, nearly encroached upon by the ambient noise and clutter aforementioned.

By contrast, Glasgow, younger than its easterly counterpart, and therefore less conducive to tourists’ fancy, was a quieter destination. It should be noted that English monarchs less-oft asserted Glasgow as part of the North; still, its story is a quintessentially Northern one. From its medieval, parochial origins—a church founded by St Mundo—it expanded, via its 15th c. university, participation in triangular trade, and, predominantly, industrialization, into ‘the second city of the British empire.’

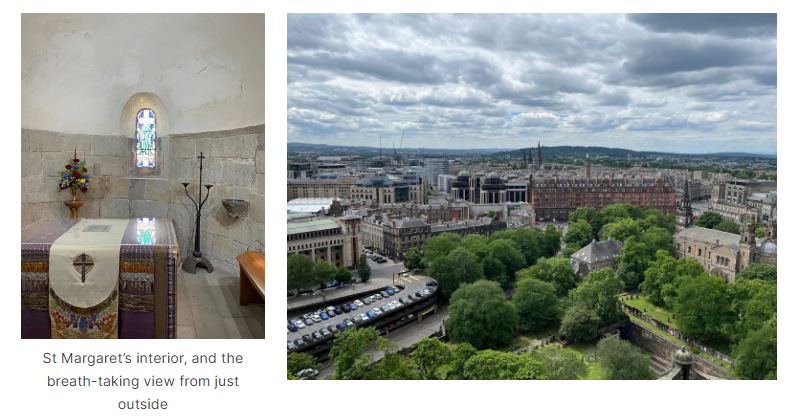

Such a status is loaded, rife with the abuses innate to imperial conquest; it is from whence Glasgow derives much of its heritage, too: global cuisine, the People’s Palace, Kelvingrove Art Gallery, GoMA, &c. Thus our Glaswegian stay was punctuated by delicious meals—the finest Indian I’ve ever eaten, Korean barbecue for lunch, and the obligatory Scottish fare (haggis, namely). Glasgow’s constituents, moreover, were some of the warmest and most amicable yr. correspondent has met.

The West End has proven, to this point, the G.I.T.’s unexpected gem: to reach the Kelvingrove Gallery therein, I had the pleasure of traversing the borough’s lively, green park, whose winding paths also lead to elegant memorials, bowling grounds, and the university. And the museum itself curated a terrific exhibition on the ‘Glasgow Boys,’ a painterly cohort born of the city’s 19th c. globalization and economic expansion. The group’s oeuvre cleverly re-considered impressionist and post-impressionist cannon(s)—for which a separate, and very solid, collection was organized, too. But, to focus so deeply on Kelvingrove is to neglect to highlight the aforesaid People’s Palace (and its meaningful documentation of Glasgow’s social history), GoMA, which punches above its weight in the modern art sphere, and the pulsating punk scene.

As this blog strays further from its (well-intended) brevity, let us now turn our attention to Durham—perhaps the key to the formation and maintenance of the North (as both idea and territory), and future home of yr. correspondent. Here, do allow me to remark more personally, since my initial visit was a surprisingly emotive one.

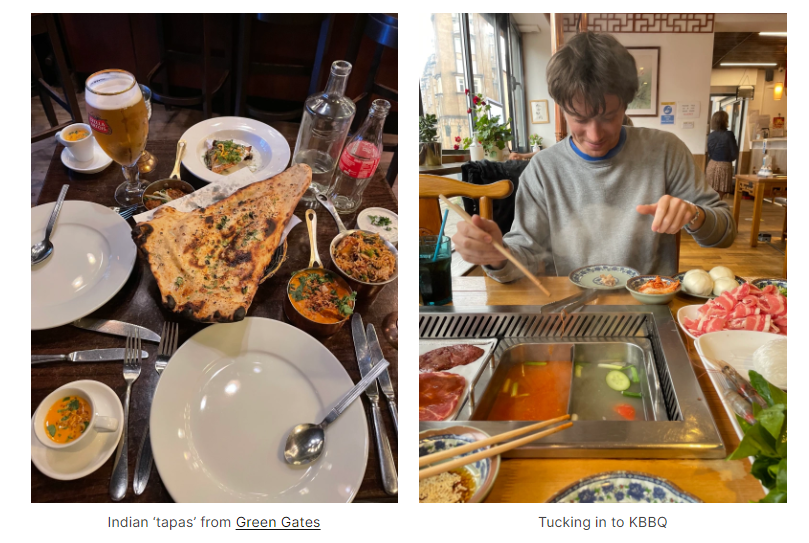

Before sentimental reflection, however, I should state that Durham Uni. was developed with the hope that the North would have a school with similar investment (and prestige) as Oxford and Cambridge. And it is truly an institution inextricable—from its re-appropriation of William the Conqueror’s castle for student accommodation, to the 11th c. Anglo-Norman cathedral used for pilgrimage, services, and research—from the foundations of Northern-ness.

Anyway: my time in Durham coincided with ‘open days,’ so the tiny city (and I) were overwhelmed by thousands of ‘freshers’ eager to open the next chapter of their life. I admit, despite our differences (primarily, age and scholastic), I experienced a sort of fellow-feeling with them: after all, I am likewise starting anew, with strangers in a strange land. In other words, I was terrified when the inherent risk of a fresh beginning was made tangible. Fortunately, I soon remembered this mix—of indeterminacy, excitement, and opportunity—from my early weeks in Alabama. (Another instance of the US South and English North aligning!)

Ultimately, I achieved a bit of solace after hearing the cathedral’s bells ringing—a constant feature of the city for nearly a millennia. It reminded me of the sheer romance of studying history where it is immediate and authentic: it is exactly why I chose Durham; and it is exactly why I am so enthralled by the prospect of this tour.

Bree’s ‘Fun Corner’:

Glasgow: Extremely friendly residents, easy to navigate, good mix of historical significance and modern fixtures. Dog viewing: 7/10, very cobblestoned, but good views to be had in almost any green space. (Best places: Green Gates Cafe, Jay’s Grill Bar, Mharsanta, Kelvingrove Art Gallery & Museum, The People’s Palace)

Edinburgh: The ability to walk through the city like those who lived in it during its prime adds to the beauty of the architecture. Dog viewing: 6/10, best only in the Meadows. (Best spots: The Meadows, Mum’s Great Comfort Food)

Newcastle: Still very industrial, but has a fun nightlife that brings individuals from further outside the city together. Easy to navigate, fun atmosphere, and overall a fun city to be in. Dog viewing: 5/10. (Best spots: Pink Lane Coffee, Mr. Mulligans)

Durham: Gorgeous city layout that, because of the peninsula and castle/cathedral, has not been changed much since its beginning. Still very intimate and small, but — like Newcastle — brings the residents together for the weekly market that hosts artisans, farmers, crafts, etc. Dog viewing: 9/10, best during the market hours. (Best spots: A walk around the peninsula, Durham Cathedral, Cafédral Durham)