The (Western) Canon

Following the footsteps of the grand tourists of yore, yr. correspondent and his associate closed their G.I.T. in Rome. For 17th c. aristocratic travelers, the Italian capital was somewhat of a fixation; for, it made manifest a key itinerant aim: exposure to the Renaissance and, more so, classical antiquity. It is indeed hard to understate how largely antiquarian concerns occupied the minds of the early modern English, even if in a patronizing light (a few visitors, oddly enough, considered Rome to be the decrepit cousin of Venice). Of course, to an extent, contemporary Americans can identify with this sentiment: we attach our cultural and political heritage, first and foremost, to Rome, not to mention ‘Greco-Roman values.’ Today, Rome’s art and architecture are oft-cited as proof of how far the U.S.—or the ‘West,’ generally—has regressed (if you are a traditionalist); or, alternatively, how sure a foundation it has built upon (if progressive is a more apt label). The city, in other words, occupies a singular place in the Western canon.

To proceed with remarks to the contrary—deconstructing the West, canon, and Rome’s position therein—is unhelpful to my ultimate point. After all, problematizing the capital’s canonical status would be, for me, intellectually dishonest, since yr. correspondent and his co. chose such a thoroughly orthodox exploratory route; we embraced simultaneously our touristic ends and the idea of Rome as a sui generis feature of European (and global) history.

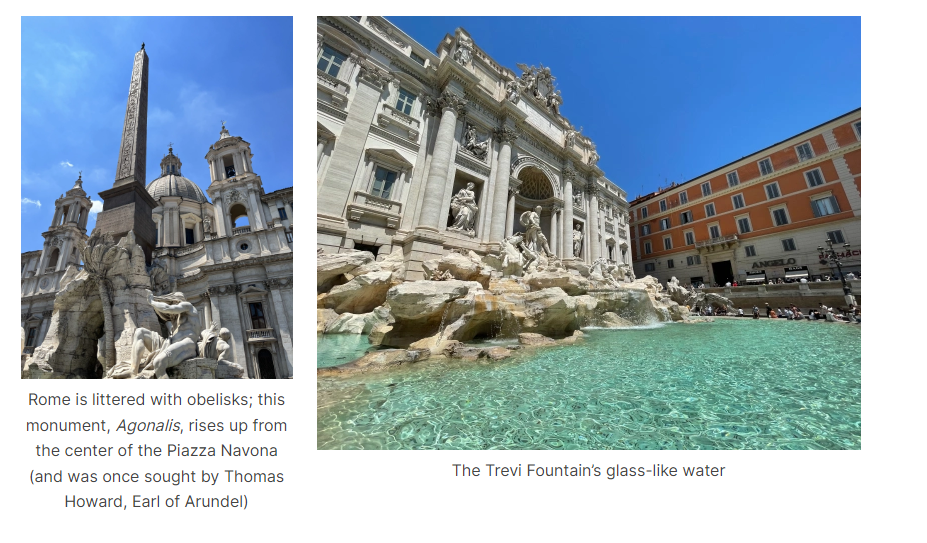

And thus our fleeting time in Rome seemed, and was, unlike anything I had ever seen (in my studies, on the trip, &c.). Our opening adventure was a self-guided saunter from the Piazza Navona to the Spanish Steps, where, from a few stories closer to the oppressive sun, we could view the whole city. To cool off, we moved to the Trevi Fountain—its Baroque sculptures were eclipsed in grandeur only by its bright turquoise water—and the Pantheon, the oculus of which obscured the mid-day sun and imbued the (astonishingly well-preserved) structure with an almost preternatural air.

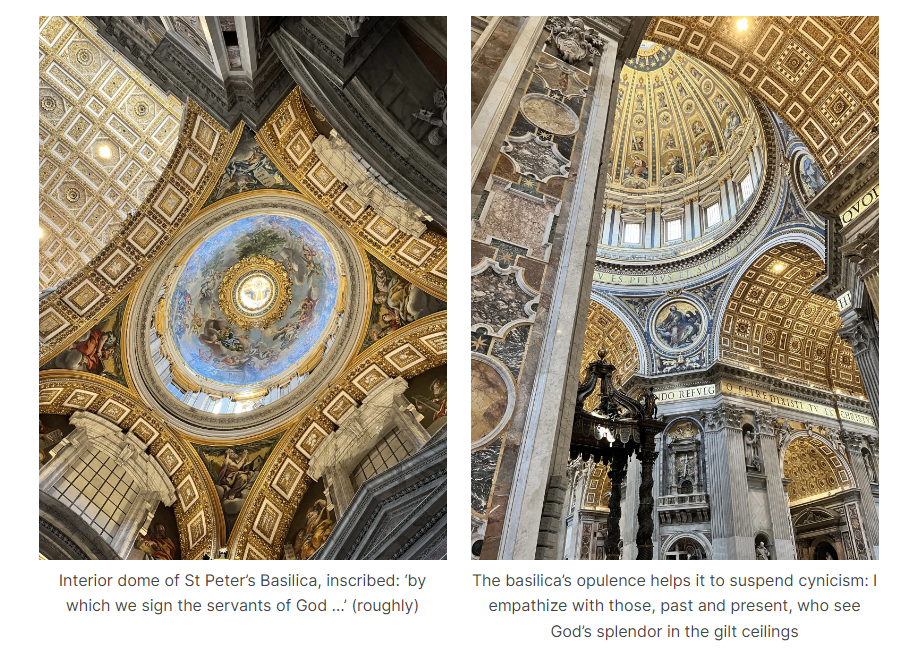

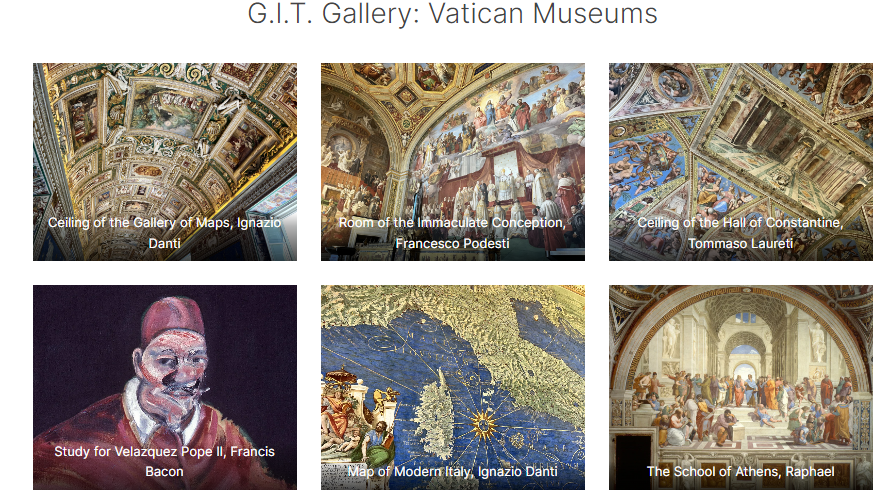

Yr. correspondent’s second day consisted in international tourism—to the Vatican. Host to millions of pilgrims (like me) annually, I imagine St Peter’s Basilica spiritually inspires all of its guests, no matter their doctrinal affiliation; and the museums nearby proved a maze of masterpieces across area, period, and discipline. Fortunate favored my associate and I for dinner, as we stumbled across a restaurant, Giulio Passami L’Olio, superlative among Rome’s excellent cuisine. Clearly adored by the locals, it took immense restraint to limit ourselves to just a couple of repeat stops.

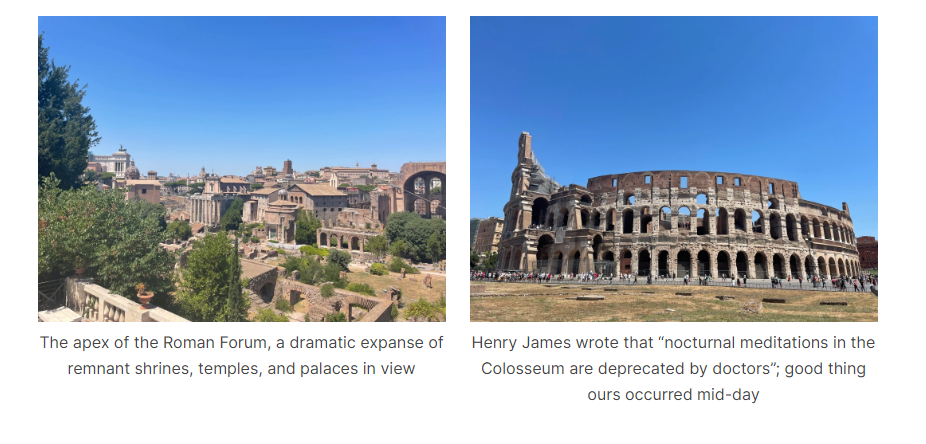

Our last bit of substantive investigation brought us to the Colosseum and Roman Forum. Here I experienced a paradigm shift of sorts: historians are a parochial bunch, often, at the expense of breadth, picturing their interests as their subject’s central (and most worthwhile) concern. Such edifices, living and breathing millennia before the Tudor England that so obsesses me, are a reminder of how little I understand, and how much I hope to learn.

But between the myriad sites of cultural import we encountered with intent and perchance, as well as the aforementioned culinary abundance (neglecting to ruminate on the finest gelato and tiramisu), a proper encapsulation of Rome would require reams and reams: the capital is better when discussed, and best when seen.

I do wish, however, to articulate a final thought on the (Western) canon. Questions respecting its revision are, as has been said, immaterial to this post; still, I sense one element of canon-modification does align well with Dr. Ramsey’s core purpose. Put simply: we should leave aside the business of the canon’s contents, and address instead to whom it applies. The answer is straight-forward: everyone who willingly associates with it. I, for instance, now believe that the Roman ruins, Parisian impressionists, Belfastian walls, and beyond—the cautionary tales they weave, lessons they represent, aptitudes they exhibit, and humanity common across space and era they demand—are part of my story. I trust Doc wanted his students and friends to feel the same, free and empowered to adopt Europe’s best ideas (and to discard its worst). I am grateful beyond words to know him through this feeling, to embody his legacy.

Early modern scholars broadly agree about the nature of the grand tour: it was a narrowly-tailored finishing school for aristocrats soon to enter crown service and high society. Yet the G.I.T., thanks to those who support it, is different: it is meant for all and it fosters the pursuit of most everything the Anthropocene has to offer. It is a finishing school for the start of a fulfilled life.

G.I.T. Gallery: Vatican Museums

Bree’s ‘Fun Corner’:

Even though our time in Rome was short, it truly lived up to the title of the Eternal City. We were able to explore all of the big names: The Vatican, the Colosseum and Roman Forum, the Pantheon, and more. The atmosphere, people, architecture, and history of the city make it such a brilliant sight that delivers on all expectations. Dog viewing: 8/10, I felt bad for a lot of the bigger dogs considering the heat, but was blown away by the small herd of Italian Greyhounds that lived near our AirBNB. (Best spots: Trevi Fountain, Vatican City, Giulio Passami L’olio, Gelateria camBIOvita Roma, Pizzeria Romana Bio, Mimi e Cocò)